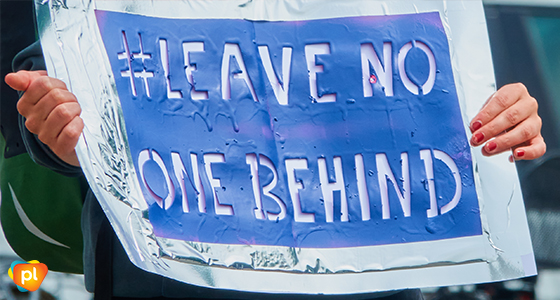

As HIV affects more communities than ever in NSW, Positive Life NSW is running with the important inclusive message ‘Leave no one behind’ in relation to HIV testing, treatment and prevention. As a woman living with HIV from sub-Saharan Africa, now employed at Positive Life NSW as a Peer Navigator supporting others living with HIV, my thoughts on this message are informed by my experience of people living with HIV in developing countries.

The majority of people who are living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa are women and children. Would you be surprised to know that according to a 2020 UNICEF report, a child contracts HIV every two minutes in this region? I am distressed by this circumstance, especially when I know there are antiretroviral drugs available in the region. I have experienced first-hand, the three main intersecting themes that contribute to this inexcusable situation, which affect not only those living 11,800 kilometres away, but impact us right here in our socially-distanced environment in NSW.

The two main levers for this appalling situation, are poverty and stigma. Let me explain. Most of the women in this situation come from very marginalised communities. They either don’t have access to HIV services or they must travel great distances to access antenatal medical care. Many of them deliver their babies at home. Most are never tested for HIV or received any antenatal care. These children are born into poverty, without any medical care or treatment, and usually into a sole parent household without employment. Women in these situations struggle to feed themselves and their children, and often need to exchange sex for an income. Once they contract HIV, even if there are HIV services nearby or antiretroviral treatments, the stigma associated with accessing this support is so extreme, they take great care to avoid these services.

Women and couples living in cities where they have access to more employment, services, or support, often live with extreme food insecurity. Many sleep hungry. Even if a person living with HIV in this environment gains access to antiretrovirals, they cannot afford to treat their opportunistic infections. I was looking at a recent documentary where people living in the city regions of sub-Saharan Africa with access to HIV antiretrovirals have progressed to AIDS quite quickly. The barrier of stigma prevents people from accessing the very medication to keep them healthy and unable to pass it on. Once again, we have the perfect storm of misery, poverty and stigma. In these communities, accessing medical care singles you out as there is ‘something wrong’. As much as the world is saying ‘Leave no one behind’, we have a long way to go before that is realised.

The third lever is the strategies we use to package health promotion information for communities from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds. In my country, beliefs and culture are quite different to mainstream Australian ways of thinking. To give an example, there is one community that genuinely believes that if a person living with HIV sleeps with a young virgin girl, they will be cured of HIV. Health promotion workers in these areas struggle to address cultural beliefs and needs without further stigmatising people from these regions. In the meantime, young women continue to contract HIV in these communities. We want to respect people’s customs and culture so they retain what is meaningful to their lives and experiences, yet we desperately need to offer understanding about what HIV is, how it is transmitted and prevented. Another example from my region, is when a husband dies, the widow is inherited by the deceased husband’s brother without any thought to the reasons behind his death. HIV is perpetuated in this way. We know that people from some regions of sub-Saharan Africa and even parts of the Asian sub-continent have little or no access to the kind of HIV treatments, care and support we often take for granted here in NSW.

If we turn to the recent COVID epidemic here in Australia, many of us are accessing the third booster shots without any difficulty, without personal cost and without stigma. Indeed in most of our communities, we are freely encouraged and supported to protect our health and that of those around us. People in some parts of developing countries have not been able to access the first vaccine.

Here in Australia, we look at each other vaccinated and boosted, wearing our face masks and adopting a number of personal holistic COVID-19 prevention strategies, and think ‘we are safe’. This is despite the fact that on the worldwide stage, we are gradually seeing new strains of COVID-19 emerging. How safe are we, when these strains originate in places of poverty and inequity?

Every month at the Positive Life Social Club, I speak with heterosexually identifying people living with HIV from CALD backgrounds who carry enormous amounts of stigma and fear even here in NSW. Recently, a woman told me directly that she cannot participate either face to face or online, because of the HIV stigma in her community here in Australia. Still today, the lever of HIV stigma negatively impacts our lives culturally and socially here in NSW.

As an island nation, we are insulated to a degree from the rest of the world. The deadly viruses of HIV and now COVID have come knocking at our door and our resource-rich country has dealt with both relatively quickly and effectively. Our resource-poor neighbours on our doorstep and those halfway around the world, have highlighted the significant challenges of saying ‘Leave no one behind’.

In illustration of this challenge, I conclude with a quote from Winnie Byanyima, Executive Director of UNAIDS on this National Day of Women living with HIV,

“We cannot have poor countries at the back of the queue. It should not depend on the money in your pocket or the colour of your skin to be protected against these deadly viruses.”

In our vibrant multicultural society we live in today, unfortunately I see the diminishing value of both shaded by persistent HIV stigma, which still has a significant reach and a greater impact than we first anticipated.