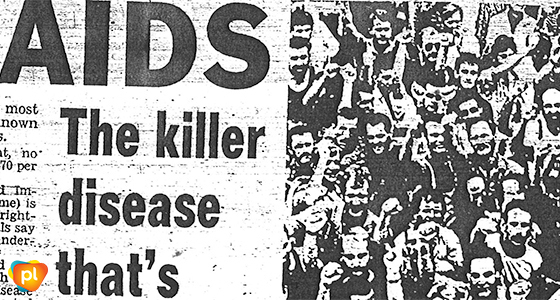

No one knew what it was, what caused it, or how to deal with it. But it was a guaranteed killer. The first recorded case of AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) in Australia was in Sydney in October 1982.

It had different names in those days. In the early 1980s – among them were ‘GRID’ (Gay Related Immune Deficiency), ‘the Gay Plague’, or simply ‘the block plague of the eighties’. Nowadays, where we know as HIV was then simply called AIDS, and its appearance at a time when gay men’s sexual and emotional lives were still illegal in most Australian states and territories meant that those most affected – gay men and their communities – were sure to be targeted.

Luckily, the gay and lesbian communities in Australia had a history of activism. From the early 1970s, the gay liberation movement had marshalled itself around a range of issues, taking on the four pillars of oppression – the church, the police, the medical profession and the media – over how they dealt with lesbians and gay men. Such an activist has provided a strong foundation for the various communities to pull together for a political response to HIV. In fact, the linkages between gay rights, human rights, and response to HIV were identified at the very beginning of Australia’s response to the epidemic.

Also important were the so-called Denver Principles, a 1983 statement of self-empowerment articulated by some Americans affected by the epidemic. They had met in Denver, Colorado and issued a clarion call to arms:

We condemn attempts to label us as ‘victims’, a term that implies defeat, and we are only occasionally ‘patients’, a term that implies passivity, helplessness and dependence upon the care of others. We are ‘People With AIDS’.

In Australia, rapid responses to the new ‘disease’ occurred in most states. 1983 saw the formation of an AIDS Action Committee (AAC) in both Sydney and Melbourne. Around this time the Victoria Prostitutes Collective had produced the AIDS peer-education pamphlet Facts on AIDS for the Working Girl. In Sydney, in an effort to put pressure on politicians to change laws, some Sydney doctors ensured that needles and syringes were provided to injecting drug users. Ita Buttrose had been appointed as the chair of the National Advisory Committee on AIDS (NACAIDS) in 1984. By 1985 the Australia Federation of AIDS Organisations (AFAO) had been formed.

There was so much to do, and so little time. People in Australia’s gay communities were dying, and there were constant attacks from the ignorant and prejudiced. There was awareness that any work in HIV prevention, care and support required an ‘enabling environment’, and this would involve working with successive state and federal governments to develop HIV strategies.

One critical early aspect was to shift the focus away from being a morality issue to a public health issue, and here the various communities were greatly helped by having pragmatic health ministers at various levels, such as Neil Blewett, the Federal Health Minister.

Getting relevant information out was an important aspect of the various communities’ and governments’ responses, and education became the key focus, for the wider Australian public as well as for those initially most affected, gay men. There were television advertisements, such as the controversial ‘Grim Reaper’ campaign of 1987, where Death, with scythe and bowling ball, mows down an Australian family. Perhaps it was ‘overkill’.

Within the gay communities there were other responses to assuage the grief and anger. Organisations to provide support were established, their names commemorating either people who had died early – such as the Bobby Goldsmith Foundation in NSW, set up in 1984 – or who had led community responses – the David Williams Fund in Victoria, set up in 1987. During this period, groups such as Ankali and Community Support Network (CSN) appeared. PLWA (People Living with AIDS) also formed groups and began organisations. AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) also emerged, protesting the delays in getting what were the few drugs available.

The epidemic was a worldwide phenomenon, and there were numerous global responses. One such was World AIDS Day, set on 1 December every year; it was conceived in 1987 by two officials at the Global Programme on AIDS at the World Health Organisation (WHO). Another response was the Quilt Project, conceived in San Francisco in 1985 and officially started in 1987. Its panels are a memorial to and celebration of the lives of people lost to the AIDS pandemic, and it was often the only opportunity survivors had to remember and celebrate the lives of their lost ones. In Australia on World AIDS Day in 1988, the first such quilt panels were displayed.

Conferences played an important role in those early years, as places for the exchange of information as well as for the contestation of ‘certainties’; perhaps one of the most important was the Third National Conference on AIDS in Hobart, August 1988. It was the scene of a dramatic development when, at the closing plenary session, a group of people walked onto the stage and declared that they were HIV-positive and that they were no longer content to remain invisible.

It was a momentous occasion: the silence of the ‘invisibles’ was broken, and a very public fight to die – and to live – with dignity was under way.

1988

Introduction, Through Our Eyes: Thirty years of people living with HIV responding to the HIV and AIDS epidemics in Australia, John Rule (Editor), p 16-17, published by the National Association of People with HIV Australia (NAPWHA) 2014.

Published for Talkabout Online #190 – March 2018