I was diagnosed with HIV during the broadcasting of the hysterical Grim Reaper campaign in 1987, at eighteen years old. My family based in southern NSW had no idea of my sexuality that I’d just started to explore. I knew very few people in the city, and only two of them I could call friends. This was a time when fear and ignorance about HIV was very much about AIDS and dying from the virus.

The year following my HIV diagnosis I was admitted to Liverpool Hospital with a brutal pilonidal sinus infection. For the first time, I disclosed my HIV positive status, outside of my small circle of friends and treatment specialists. My family were none the wiser to my admission or that I was living with HIV.

During that three-week admission, I experienced HIV stigma, discrimination, and ignorance first hand on a daily basis. I was told that I was the first ‘AIDS patient’ at the hospital. The fear on some of the clinician’s faces was palpable and only served to reinforce my own subconscious fears. I was not taking any HIV meds at the time, as anti-retroviral treatment (ART) was not yet available.

They put a big red sign above my bed which said “Highly Infectious”. I demanded they take it down, which they did, and placed it in the medical record folder hanging at the end of my bed.

One evening there was a heated argument between the kitchen staff and the nurses at the end of my bed. The kitchen staff refused to remove my food trays and utensils even with gloves on. The nurses said it was not their responsibility to remove patient food trays. This argument in front of me brought me to tears. The final resolution to this fearful argument was that all my food waste, trays etc were to be wrapped in plastic bags by the nurses and then removed by kitchen staff. Where it went and what happened to it, I don’t know.

Staff sometimes would come in, find me in that shared ward and stare at me with distaste written across their face and then walk out, without a word of explanation. It was one of the loneliest, most isolating experiences of my life. My two friends, Colin and Bill visited one day travelling all the way from the inner city.

Surgery to clean the infection and relieve the pressure on my spine was next. Preparations were communicated to me with the first procedure being to shave the area around my lower spine. The assistant in nursing refused to shave me, this turned into another argument. The whole process of going into theatre was delayed several times. Overall these incidents were intensely painful. The feelings from this period have stayed with me my entire life. I still get emotional thinking about it today. It never goes away.

Fast forward 31 years later, I’m on holiday in Far North Queensland (FNQ). I’m seriously ill with fatigue, dehydration, fevers, rigours and intense migraines. I’m admitted to hospital for the next four days and treated with IV fluids, analgesia and high dose Flucloxacillin, the standard antibiotic treatment for diseases such as Dengue, Ross River, and Q fever. I temporarily lose a third of the sight in my right eye.

Throughout my stay, I’d been open to everyone about my HIV positive status. I even found myself conducting ad-hoc educational in-services with the nurses and other clinical staff about general HIV treatment options, viral loads, undetectable viral load in relation to transmission, and treatment as prevention (TasP). None of them knew anything about these developments. I really owned my health conditions in the hospital. I felt empowered and comfortable speaking about HIV the whole time. I want to thank the staff for looking after me so well, even providing me with clothes to wear on my discharge.

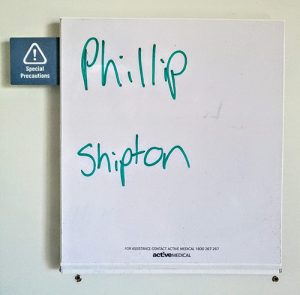

Upon discharge, I notice a small sign, approx. three by three centimetres, on the whiteboard above my bed. It has a small white triangle around a white exclamation mark with the words ‘Special Precautions’.

Now, as soon as I saw that, my heart started racing. Flashbacks came all at once, it was a subconscious trigger that took me back to my early traumatic experiences in the hospital with HIV.

Now, as soon as I saw that, my heart started racing. Flashbacks came all at once, it was a subconscious trigger that took me back to my early traumatic experiences in the hospital with HIV.

I didn’t have the strength to find out what it was about. I was physically and mentally weakened from the previous four days and didn’t want to cause a fuss before my discharge. I was picking my battles at that time. I took a photo of it, put it on Facebook with a brief comment, packed my belongings and left the hospital.

The photo drew plenty of comments and sparked a few opportunities for discussion and support. A few days later, a colleague working in the health sector training medical students contacted me. He told me the sign had nothing at all to do with HIV. It was a new standard procedure for anyone with suspected respiratory or viral illness. What a relief the issue had been resolved.

I volunteer in the HIV sector today and know that people who own their HIV status are less prone to HIV stigma. My own experiences over the years have taught me that whenever I own my HIV positive status, I normalise it and I don’t agonise with feelings of stigma. In fact, I’m helping to change people’s perceptions about people living with HIV. I’m quite capable of educating them and happy to answer any questions if I have the chance.

Yet, that flashback took me by surprise.

I was shocked by the strength of that perceived stigma. That old sense of powerlessness and hopelessness I felt when I was nineteen. There was no medication in those days. There was only fear about contracting a deadly condition, there was my fear about dying. I felt powerless in the FNQ hospital, it all came back like it was yesterday. I felt impacted by what happened all those years ago.

That little sign, was a haunting reminder of what happened back in 1988. Some people living with HIV today are not comfortable talking about their HIV openly. I think some of us are still internalising that fear of the virus, of dying, of being mistreated, and we internalise that fear in ourselves. We don’t do ourselves any favours by doing that. I think perceived stigma and internalised stigma are very much inter-related.

Being open about living with HIV and making it a new kind of normal for us, whether it’s perceived or real stigma, helps to move through the pain. Looking back, I think the experience has made me stronger.

Phillip Shipton

Phil Shipton was a 2017/18 Positive Life NSW Board Member

Published for Talkabout Online #191 – December 2018