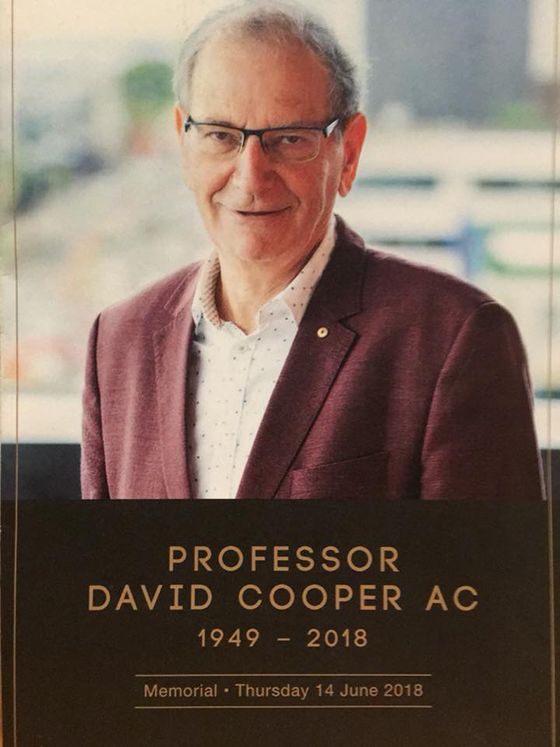

I stand before you today, to honour and remember Prof David Cooper, who I’ll refer to hereafter as Coops.

Speaking as a patient, when I was diagnosed with HIV in 2004, I polled my friends and asked who the recommended HIV doctors were. Coops came out as the preferred doctor, so I asked my GP for a referral. On my first meeting with David, I was impressed by his warmth and caring, yet mindful and systematic approach to my healthcare. Immediately, I was put at ease and over time, a respectful rapport began to grow.

My nature is to worry, and the HIV diagnosis gave me a whole new set of worries. The intriguing thing was, Coops had a knack to carry my worry for me. Usually, when I see someone worried about me, I likewise feel anxious and concerned. This wasn’t the case with Coops. There were four times over the years where I was doing it tough, and things were going wrong with my: HIV treatments, recurring staphylococcus abscess, a hepatitis C diagnosis, and hep C treatment failure. In these moments, Coops would become quiet and considered. His worried and considered manner would result in an immediate feeling of ease, rather than distress. I trusted Coops implicitly. He was the essence of what we look for in a good doctor, as many others could attest. I knew I could rely on him, to do what was needed, so I remained healthy and alive. His dedicated loving care resulted in a familiar patient doctor understanding. He was Coops and I was Coops number 2.

Coops made it possible for me to communicate with him regularly and frequently via email, telephone and during clinic appointments. The open and accessible communication built a comfortable relationship, which eventually turned into friendship. Nothing was ever too much trouble, Coops was always there for me.

When we were going through the decision-making process about starting HIV treatments, Coops gave me the space and time I needed to think through my options and make the decision. If I’d felt coerced or pressured, I wouldn’t have started treatment immediately and would have become much sicker.

Coops had a way of making his patients feel completely at ease, even though we were often dealing with ‘complex’ medical issues. I recall I was concerned about a problem I was having in a sensitive area of my body. Knowing Coops would sort it out; I walked into the consult room at St Vincent’s and started to undress, to show him what I was concerned about. Coops was only momentarily startled as he looked up from behind his desk and enquired what I was doing. As it’s not standard practice to undress for a HIV consultation. But in that moment, I learned it was almost impossible to shock Professor David Cooper. And that’s what made him such an excellent doctor.

To finish the story, it turned out I had cellulitis of the genitals, but nothing a quick course of antibiotics couldn’t fix.

When I received a hepatitis C diagnosis in 2016, Coops was helping me work out who I had to contact, as I may have placed others at risk sexually. I worked out a ranking order of risk among casual sex partners and regular guys I’d go to sex parties with. In one email Coops replied with ‘You have a very high hepC viral load (not unexpected for initial infection) so please be careful with the brachio-proctic eroticism!!’ His way of describing an esoteric sexual practice – very David!!

Coops had a wicked sense of humour, which grounded him in life’s eccentricities. He would quickly pick up and use peoples nick names and crack jokes, for example Saquinavir was jokingly referred to as ’save a queer’.

Speaking as a community member, we owe so much to the work of Coops and there Kirby Institute. His work with Brett Tindle in documenting sero-conversion illness; the identification of lipodystrophy; his extensive clinical trials and treatment experience; and more recently his PrEP leadership.

Coops’ ability to translate detailed scientific information into targeted strategic language that we as community partners could access and work with was inspiring. Just like his ability to translate the varied colourful language describing esoteric sexual practice, into concise medical terminology.

As Coops was often travelling abroad, and he liked to keep abreast of things, as a way of keeping track of what was happening, and understanding the sector. During doctors’ appointments and sector meetings, we’d talk about what was happening in the community and what the issues were. We’d have conversations about advocacy and how the community would receive scientific or health policy recommendations.

Coops’ devotion to his life calling made him not only a doctor to me, but a doctor to our community. David’s commitment to a diverse array of patients was heart-warming. Examples of some of his patients were: sex workers; people who use drugs; Aboriginal people; Women, Men and Trans-people living with HIV; Gay Men; and people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. His leadership in the sector is sorely missed.

On behalf of Coops patients and my HIV sector colleagues – Dorrie, Ilana, Bec – I’d like to acknowledge your family’s contribution, for the hours of family life he’d missed, with his nearest and dearest. Your love and devotion replenished and nurtured Coops, enabling him to achieve greatness and be the extraordinary affable leader that he was.

Coops cared for thousands of people, in Australia and internationally, who would not be alive today if it were not for his work. His legacy will live on, he will be remembered. He was not only my doctor, but a doctor to our communities.

Click to watch David Cooper Memorial Livestream from the Kirby Institute website

SBS World News (14th June 2018) – 51.28